Why Most Legacy Modernization Fails in Year Two — And What Successful Programs Do Differently

Why Most Modernization Programs Look Successful in Year One

In the first year, most legacy modernization programs appear to deliver exactly what they promised. Systems are migrated, outages decline, and stakeholders see tangible progress. Executive dashboards turn green. Project teams declare success. In many cases, the technical work is genuinely solid.

This early success is driven by intense focus and concentration of expertise. Senior architects, legacy SMEs, compliance specialists, and delivery leads are deeply embedded during the transformation. Decisions are made quickly because the right knowledge is present in the room. Risks are mitigated through manual oversight and heroics rather than durable structures.

Modernization metrics also favor short-term validation. Programs are judged on cutover stability, performance benchmarks, and immediate cost reduction. These indicators matter, but they measure execution quality, not long-term viability. Very little attention is paid to what happens after the project team rolls off.

Once go-live is achieved, the model shifts abruptly. Delivery teams disband. External partners move on to the next engagement. Internal teams inherit modernized systems with limited context beyond static documentation and high-level diagrams. The assumption is that “modern” systems will be easier to operate and evolve on their own.

This is where the illusion forms. In year one, stability is propped up by residual project momentum and the availability of people who still remember how things work. The real test—operating, changing, and governing the system without that concentrated knowledge—has not yet begun.

Year-one success, in other words, is not a guarantee of modernization success. It is merely the end of the first act. The structural weaknesses that determine long-term outcomes typically surface later—when change resumes, regulations evolve, and the original knowledge dissipates.

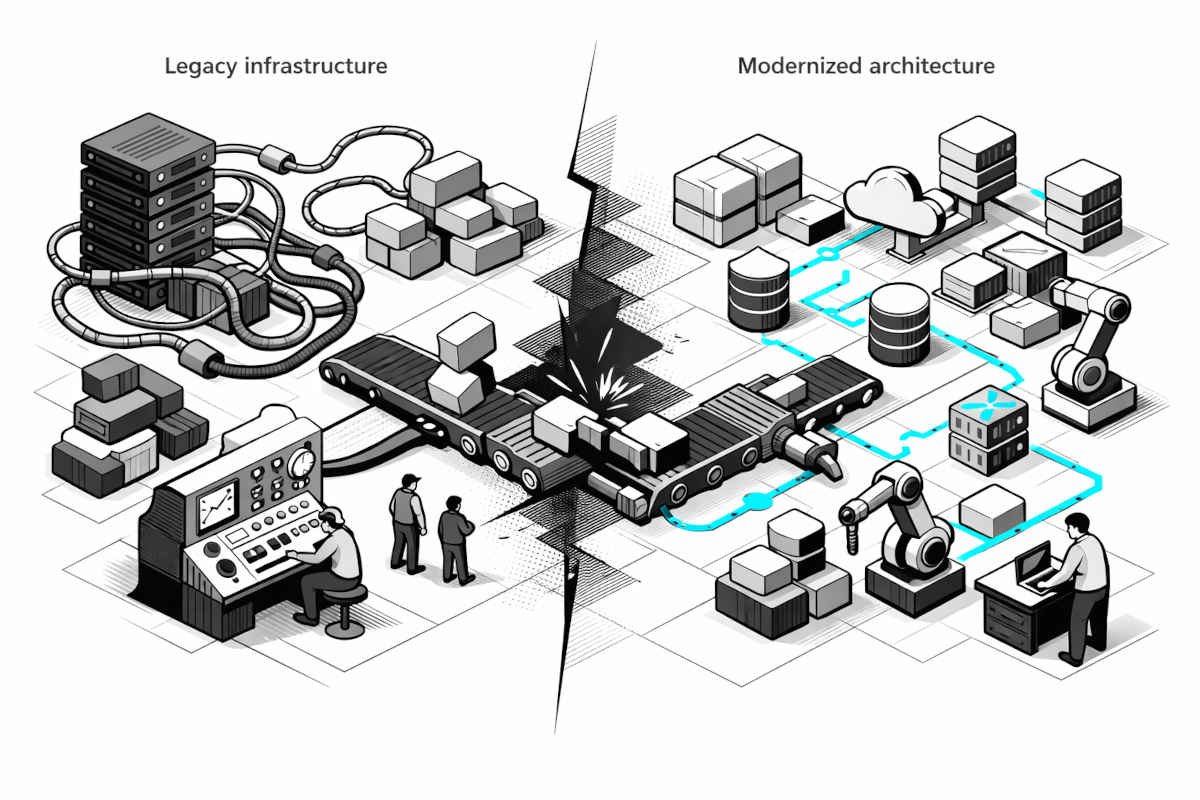

The Year-Two Breakdown: Where Modernized Systems Start to Decay

The second year after modernization is where many programs quietly begin to unravel. The initial stability achieved at go-live gives way to friction as systems are asked to change, integrate, and comply under real operating conditions—without the safety net of the original delivery team.

The first signs appear in change velocity. Simple enhancements take longer than expected. Release cycles slow as teams struggle to understand unintended side effects. Engineers become cautious, adding layers of testing and approvals to compensate for uncertainty about system behavior.

Integration fragility follows. Modernized cores are often surrounded by legacy and third-party systems that continue to evolve. Without clear visibility into dependencies and data flows, even minor interface changes introduce outages or require extensive manual coordination. What was once positioned as a flexible, modern architecture begins to feel brittle.

Compliance teams feel the impact next. New regulations or audit requests require explanations of system behavior, data lineage, and control logic. Without living system knowledge, teams revert to manual analysis, interviewing former project members, or reverse-engineering code. Audit preparation timelines stretch, and risk exposure increases.

Operational costs also creep back in. Incidents take longer to diagnose. Root-cause analysis becomes speculative. Knowledge gaps force organizations to re-engage expensive external expertise—often the same partners who were involved in the original modernization.

None of this is usually labeled as “failure.” Systems continue to run. Business operations proceed. But the promised benefits of modernization—speed, resilience, and reduced risk—begin to erode. The organization finds itself maintaining a modernized system with legacy-era uncertainty.

At this point, many enterprises assume the problem lies in tooling choices or architectural decisions. In reality, the decay is driven by something more fundamental: the loss of shared system understanding.

The Real Failure Mode: Loss of System Understanding, Not Technology

When modernization programs falter in year two, the instinctive reaction is to question technical choices. Teams revisit cloud platforms, microservice boundaries, or vendor tools. While these decisions matter, they are rarely the root cause of long-term failure.

The real failure mode is loss of system understanding.

During modernization, understanding is concentrated. Architects know why certain decisions were made. Developers understand edge cases embedded in migrated logic. Testers know which scenarios required special handling. Much of this knowledge lives in people’s heads or in artifacts created for delivery, not for long-term use.

Once the project ends, that understanding dissipates. Documentation freezes. Diagrams age. Key individuals move on. What remains is code that may be clean and modern, but opaque in behavior. Teams are left managing systems they technically own but do not fully understand.

This gap shows up in everyday operations. Engineers hesitate to change logic because downstream impact is unclear. Compliance teams struggle to trace data flows across services. Architects design integrations based on assumptions rather than verified behavior. Over time, risk aversion replaces agility.

Technology does not cause this outcome. Modern platforms can support observability, automation, and scalability. But without preserved system intelligence—clear, current knowledge of how the system behaves—those capabilities are underutilized.

Successful modernization requires more than moving code to a new stack. It requires ensuring that understanding survives the transition and continues to evolve. When knowledge decays, modernized systems begin to exhibit the same fragility and inertia as the legacy platforms they replaced.

This is why year-two failure feels so confusing. The system is new, yet the organization is back in familiar territory: slow change, rising risk, and increasing dependency on a few experts.

The consequences of this knowledge loss become even more severe in regulated environments, where understanding system behavior is not optional—it is mandatory.

How Compliance, Integration, and Change Velocity Suffer Over Time

As system understanding erodes, the impact is felt most sharply in areas that demand precision and confidence: compliance, integration, and the ability to change quickly. These are not abstract concerns; they directly affect operational risk and business outcomes.

In regulated industries, compliance depends on explaining how systems behave—not just how they are designed. Auditors ask where sensitive data flows, how controls are enforced, and what happens under exception conditions. When system intelligence is fragmented or outdated, answering these questions becomes a manual exercise. Teams reconstruct behavior through interviews, code reviews, and ad hoc testing, increasing both cost and regulatory exposure.

Integration work becomes similarly fragile. Modernized systems rarely operate in isolation. They are continuously integrated with upstream and downstream applications, external partners, and new digital channels. Without clear visibility into dependencies and data transformations, even small integration changes require excessive coordination and conservative assumptions. Integration velocity slows, and the risk of cascading failures increases.

Change velocity across the organization declines as uncertainty grows. Development teams compensate for incomplete understanding by adding layers of process—extended testing cycles, additional approvals, and defensive coding practices. What began as a modern, agile platform gradually acquires the same operational friction as the legacy environment it replaced.

These effects compound over time. Compliance work becomes more expensive. Integration projects take longer to justify and deliver. Innovation initiatives are delayed or scaled back due to perceived risk. The enterprise does not experience a dramatic failure, but it quietly loses the advantages modernization was meant to deliver.

At this stage, organizations often conclude that modernization “didn’t work as expected.” In reality, it worked exactly as designed: it modernized technology without preserving the intelligence needed to operate and evolve it.

Some enterprises, however, break this cycle. They design modernization programs not just for year-one delivery, but for what comes after. The difference lies in what they deliberately preserve once migration is complete.

What Successful Programs Preserve After Migration

Organizations that avoid year-two failure approach modernization with a broader definition of success. For them, migration is not the finish line—it is a transition point. What matters most is what remains once the delivery team steps away.

First, successful programs preserve behavioral knowledge. They ensure that business rules, exception handling, and control logic are captured in a form that survives beyond individual contributors. This knowledge is not locked in static documents, but represented in ways that can be queried, validated, and updated as systems evolve.

Second, they preserve contextual traceability. Code changes, data transformations, and integration points are linked back to business processes and regulatory requirements. When something changes, teams can understand not just what was modified, but why it matters. This traceability reduces risk and accelerates impact analysis.

Third, they preserve shared visibility. Architects, developers, operations, and compliance teams work from the same understanding of system behavior. This shared foundation reduces friction between functions and prevents the re-emergence of silos that slow decision-making.

Importantly, successful programs also preserve ownership. Responsibility for system understanding does not disappear when partners roll off. It is embedded into governance models, tooling, and operating practices. Knowledge is treated as an enterprise asset, not as a project byproduct.

These preserved elements create resilience. When regulations change, teams can respond with confidence. When integrations are added, dependencies are visible. When new developers join, onboarding time is measured in weeks rather than months.

The contrast is stark. While failing programs inherit modern code with legacy uncertainty, successful ones inherit a living understanding of their systems. That difference determines whether modernization delivers lasting value—or simply defers the next transformation crisis.

This naturally leads to the question of how organizations operationalize this preservation at scale. The answer lies in treating system intelligence as a continuous capability, not a one-time output.

Why Continuous System Intelligence Separates Survivors From Strugglers

The defining difference between modernization programs that endure and those that decay is continuity of system intelligence. Survivors do not assume that understanding, once captured, will remain valid. They design for continuous insight as systems evolve.

Continuous system intelligence means that behavioral knowledge is updated alongside code changes. When integrations shift, data flows change, or controls are modified, those changes are reflected in the system’s intelligence layer. Teams are not forced to rediscover reality after the fact; they see it as it changes.

This continuity transforms how organizations operate. Change impact analysis becomes faster and more reliable. Compliance teams gain ongoing visibility rather than periodic snapshots. Engineers work with confidence because they understand how their changes propagate across the system.

Struggling programs, by contrast, rely on episodic rediscovery. Intelligence is rebuilt during audits, incident investigations, or the next modernization initiative. Each cycle increases cost and risk, reinforcing the perception that modernization is inherently disruptive.

From a governance perspective, continuous intelligence shifts accountability. Knowledge ownership is no longer tied to individuals or project phases. It becomes part of the operating model. This reduces dependency on heroics and makes modernization more resilient to personnel changes.

The payoff is compounding. Each year that intelligence is maintained, future work becomes easier. Integration accelerates. Compliance stabilizes. Change velocity improves. Modernization begins to deliver on its original promise—not just in year one, but over the long term.

Enterprises that recognize this early redesign their modernization approach accordingly. They plan explicitly for year two and beyond, embedding intelligence preservation into how transformation is governed and executed.

How Enterprises Redesign Modernization for Year-Two Success

Enterprises that achieve durable modernization do not rely on hope or heroics. They redesign their programs with the explicit assumption that risk, change, and regulatory pressure will continue long after go-live. Year-two success is engineered, not accidental.

The first shift is redefining success criteria. Leading organizations measure modernization outcomes beyond cutover stability. They track how quickly teams can explain system behavior, assess change impact, and respond to regulatory inquiries months after delivery. These indicators force attention on knowledge preservation, not just technical completion.

The second shift is embedding intelligence ownership into governance. Responsibility for system understanding does not end with the project. Enterprises assign clear ownership for maintaining behavioral insight as systems evolve—often spanning architecture, engineering, and risk functions. This ensures that intelligence remains current and trusted.

Third, successful programs standardize how knowledge is captured and reused. Instead of allowing each engagement to generate bespoke artifacts, enterprises adopt platforms and practices that continuously extract, validate, and update system intelligence. This reduces variance across teams and prevents knowledge fragmentation.

There is also a delivery model change. Rather than disbanding teams entirely, organizations maintain continuity across phases. Core members transition from migration execution to ongoing modernization stewardship, carrying forward context and decisions. Partners are engaged not just to deliver projects, but to help institutionalize intelligence.

Finally, enterprises redesign funding and planning assumptions. Modernization is treated as an ongoing capability investment rather than a finite program. This allows incremental evolution, smaller changes, and fewer disruptive transformations.

These structural shifts do not eliminate complexity—but they make it manageable. By planning for year two from day one, enterprises turn modernization from a risky event into a controlled, repeatable process.

One final principle ties all of this together: modernization must be designed for what comes after go-live, not just for the moment of transition.

Modernization That Lasts: Designing for What Comes After Go-Live

The true test of modernization is not the success of the cutover, but the resilience of the system in the years that follow. Enterprises that design exclusively for go-live optimize for a moment in time. Those that design for what comes after build lasting capability.

Modernization that lasts assumes change is constant. Regulations evolve. Integrations multiply. Business priorities shift. In this reality, the most valuable outcome of modernization is not new technology, but sustained understanding of how that technology behaves under real-world conditions.

Programs that endure treat system intelligence as a permanent asset. They invest in capturing behavioral knowledge, maintaining traceability, and ensuring shared visibility across technical and non-technical teams. As a result, they reduce year-two risk, preserve change velocity, and avoid slipping back into legacy-era uncertainty.

This approach also reframes the role of modernization partners. The most effective partners are not those who simply deliver migrations, but those who help enterprises institutionalize intelligence—leaving behind systems that can be confidently governed, evolved, and audited.

Year-two failure is not inevitable. It is the predictable outcome of modernization models that end at go-live. By designing for continuity, enterprises can ensure that modernization delivers on its promise long after the project is complete.

Modernization doesn’t fail at cutover. It fails when knowledge disappears.